HAMILTON, ONT. -- Climate change is a top-of-mind issue for many Canadians heading into the federal election and that has only been fuelled by sweltering weather felt across much of the country, flooding in the Yukon, and devastating forest fires in British Columbia and Ontario.

Evidence is mounting that the world is on a tipping point of catastrophic damage. A grim Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report released in August, was deemed a “code red for humanity,” by the United Nations.

Canada has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40-45 per cent over the levels of 2005 by 2030 and to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. But in 2019, the latest year for which numbers are available, Canada was closer to those 2005 numbers than to where it has promised to be in less than a decade.

Canada has instituted carbon pricing – often called a carbon tax – in an effort to curb emissions that will be $50 on a tonne in 2022 and increase by $15 per tonne until it reaches $170.

- Election Dispatch: Sign up for a daily update on the campaign

- 2021 platform guide: Where do the parties stand?

THE CLAIM

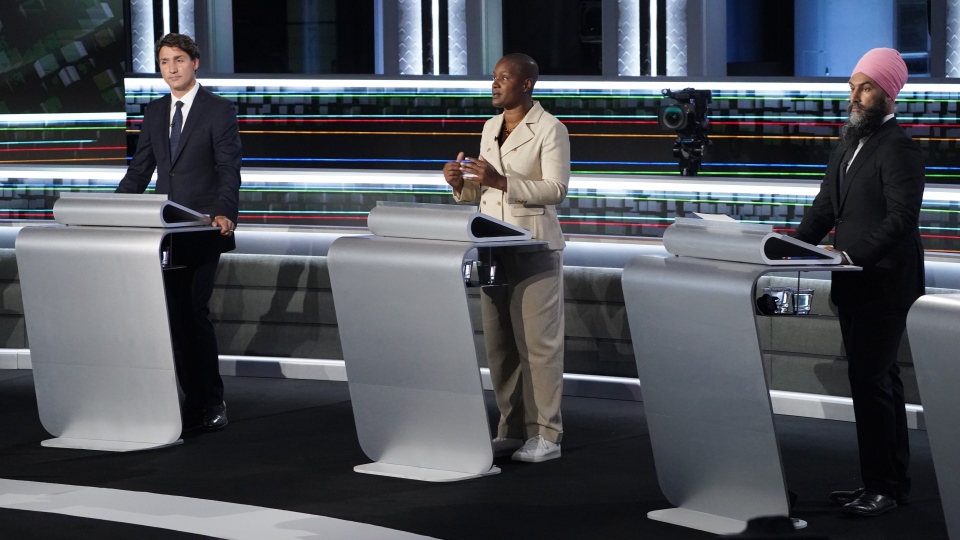

On the campaign trail and during Wednesday’s leaders’ debate, NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh has said that emissions have gone up during Justin Trudeau’s time as prime minister.

During the debate, in response to a question about reducing fossil fuels from an 11-year-old boy from Quebec, Singh said: “This is an issue we have to tackle head on. Mr. Trudeau said that he wants to reduce emissions. Every target has been missed.”

Singh also said during a campaign stop in Toronto this week that Canada has become the worst emitter in the G7 under Trudeau’s leadership.

"Our plan is to fight this climate crisis like we really want to win it," Singh said.

BACKGROUND

According to the United Nation’s yearly Emissions Gap Report released in 2020, global greenhouse gas emissions grew for the third-straight year in 2019 and that the world is still heading for a temperature increase in excess of 3 C this century, well beyond the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to well below 2 C.

The report says Canada is among five G20 nations projected to fall short of its commitments, along with the United States, Australia, Brazil, and South Korea

In a report released in July, called All Hands on Deck, the Pembina Institute and Simon Fraser University argued that without aggressive, targeted and coordinated plans by the federal and provincial governments, Canada will fall short of its emission reduction commitment.

It found overall greenhouse gas emissions dropped by just 1 per cent between 2005 and 2019.

ANALYSIS

Singh is right that greenhouse gas emissions have ticked up during Trudeau’s time leading the country.

According to the federal government’s own numbers, in 2016, the first full year of Trudeau’s mandate, Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions were 707 million tonnes (megatonnes) of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Those levels rose to 716 in 2017, 728 in 2018 and 730 in 2019, the latter being the first year of the federal carbon tax. The Liberals say the real effect of carbon pricing will be seen in coming years.

The numbers for 2020 have not been released, but there is expected to be a drop due to the effects of pandemic lockdowns on production.

“Almost for sure we will see a drop in emissions but that has nothing to do with policy and everything to do with COVID interrupting production in places like the oil patch,” said Dale Marshall, national climate program manager with Environmental Defence Canada.

Canada has long played fast and loose with emissions numbers, Marshall said in a phone interview from Ottawa with CTVNews.ca.

The Harper government shifted the baseline year for emissions tracking from 1990 when they were lower (around 600 megatonnes) to 2005 when they were higher (730 megatonnes). Many other jurisdictions continue to use 1990 levels, meaning their reductions are even greater relative to Canada’s.

Nic Rivers, a professor at the University of Ottawa, says the effects of carbon pricing, fuel economy regulations and the decommissioning of coal-fired electricity plants across much of Canada are just ramping up. Carbon pricing is starting slow to prevent shocks to the economy, so the effect will grow in years to come, he said in a phone interview with CTVNews.ca.

“This is like turning around the Titanic. Almost everything around us contributes to this, from cars to the furnace in my house to steel making and the urban form itself.”

Marshall says while some point out that Canada’s population has grown at a faster rate than parts of Europe and the United Kingdom, which have cut emissions much more aggressively, he says that isn’t a significant factor.

About 25 per cent of Canada’s GHG emissions are directly tied to production in the oil and gas sector and since the vast majority of that is exported, domestic population growth isn’t relevant, Marshall says. Another 25 per cent of the country’s climate change-causing emissions are linked to transportation and a big factor there is a consumer shift from smaller cars to SUVs and pickup trucks, he adds.

For Marshall, carbon pricing is an important measure in cutting Canada’s emissions, but it must be more stringent and further-reaching. As designed, between 80 to 95 per cent of industrial emissions are exempt and weaker provincial regimes in Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan and New Brunswick have been allowed to take precedence over federal regulations.

The International Energy Agency reported in May that global net-zero emissions targets are not achievable without an immediate halt on any expansion of the oil and gas industry.

Among Canada’s election contenders, only the Green Party has that in its platform.

It’s a politically fraught issue on so many levels, says Rivers, who is Canada Research Chair in Climate and Energy Policy.

“It’s probably the biggest question in Canada and there is no easy answer to it… There are so many jobs and identities tied up in that industry and it’s so geographically concentrated.”

Marshall expects that international pressure will play a role in forcing Canada to adopt stricter measures to meet climate-change goals.

“We are sensitive about what the global community thinks of us and we want to be seen as good actors on the international stage,” he said. “And it’s kind of undeniable that Canada is a laggard when it comes to climate change.”

But is Canada the worst emitter among G7 nations, as Singh contends?

That mostly checks out, too.

Yes, the U.S., the European Union, and Germany emit more greenhouse gases than Canada in absolute terms, but Canada has the dubious distinction of seeing the greatest leap in emissions at 3.3 per cent between 2016 and 2019.

That beat out the United States at 0.6 per cent and fell exponentially short of the five other G7 nations that cut GHG emissions between 4.4 and 10.8 per cent.

But Marshall says he has confidence in the mobilization of Canadians, especially driven by young people, who understand the urgent need to combat climate change.

“People understand that this isn’t the distant future. It’s here now and on our shores.”

CONCLUSION

Singh’s claims check out. Canada’s GHG emissions have grown since Trudeau took office, though there is an expected drop in 2020 numbers yet to come, largely due to the pandemic. And among Canada’s G7 allies, it has been the worst performer when it comes to cutting emissions during the Liberals’ time leading the country.

Edited by Adam Ward